In 1637, the pregnant wife of the head of Kuchinotsu was killed on orders from the Magistrate because her husband was unable to pay his land taxes. This incident sparked a number of revolts by villagers of the Shimabara Peninsula and the district of Amakusa. The person who would come to lead the masses was Shiro Amakusa, a young man just fifteen or sixteen years of age.

To the shogunate government and other powers, this was seen as nothing more than a minor peasants’ revolt. However, the rebel forces were led by the former samurai who had been retainers of Christian Daimyo such as Arima and Konishi and were fully armed and well-organized. The situation grew more and more serious.

Due to poor harvests and the cruel land taxes imposed by the Matsukura Clan, many on the Shimabara Peninsula began dying of starvation. It was said that everything had been taken away from the citizens except the rice seed needed for the next year’s planting. In private conversations, the former samurai of the Arima Clan, men who had given up their titles and become farmers in order to remain on the Shimabara Peninsula, began talking more and more about “needing to do something about the miserable situation.”

The citizens of Shimabara Peninsula were not the only ones enduring these kinds of hardships. Also suffering from heavy land taxes and the ban on Christianity were the people of Amakusa, a region now governed by Karatsu feudal lord Hirotaka Terazawa. Terazawa had replaced Christian daimyo Yukinaga Konishi after the latter suffered defeat in the battle of Sekigahara. Furthermore, in Amakusa close attention was being paid to the words of Christian missionaries who had prophesized that, “When a great calamity threatens the people with annihilation, a sixteen-year-old Child of God will appear to save all those who believe in the teachings of Christ.” The Christian ronin (masterless samurai) who had served as retainers for Yukinaga Konishi now banded together under this prophecy.

The former samurai of Shimabara Peninsula and the Christian ronin of Amakusa then gathered together on Yushima, the island that rose up in the sea between their lands. Here the two forces united and drew up plans for a rebellion.

Yushima (the island of unification), as seen from the Shimabara Peninsula

Yushima (the island of unification), as seen from the Shimabara PeninsulaWhile plans for a rebellion were being drawn up on Yushima, an incident that would ignite the anger of the local people took place. This was when the magistrate issued orders that the pregnant wife of the headman of Kuchinotsu be killed for her husband’s inability to pay the land taxes. The manner of death for the woman and her unborn child was particularly brutal, as she was confined in a basket and submerged in the icy waters of a river in wintertime.

This incident would prompt the people of Shimabara Peninsula and Amakusa to stage a series of revolts. The leader of their campaign would be Shiro Amakusa, a young man just fifteen or sixteen years old. Believing that this was the “Child of God” that the missionaries had prophesized, the Christians publicly proclaimed their faith and stood up to confront their feudal lord.

The uprising citizens of the Shimabara Peninsula besieged Shimabara Castle, the base of the Matsukura Clan, while those in Amakusa moved in on Tomioka Castle. The former samurai who led the group made sure that the villagers were armed and organized. Far from being a mere peasants’ revolt, the situation was now developing into a full-scale battle.

Statue of Shiro Amakusa (at the ruins of Hara Castle)

Statue of Shiro Amakusa (at the ruins of Hara Castle)The rebelling citizens gained momentum early on, but were unable to take over Shimabara Castle and Tomioka Castle. The forces in Amakusa then crossed the sea in order to unite with their counterparts on the Shimabara Peninsula. In total, they numbered 37,000 people. Forming a huge group that consisted of women and children as well as the warrior men, they moved en masse to the ruins of Hara Castle and took refuge there. Most likely they had heard about how the Society of Jesus had repelled the forces of the Ryuzoji Clan with their guns and thought, “If we can just hold on here for a while the Portuguese ships will surely come to our aid.” With that hope in mind, the people banded together and began living in an organized manner while confined in the castle.

The shogunate had initially viewed this uprising as nothing more than a minor revolt, but when the seriousness of the situation became evident daimyo across Kyushu were contacted and told to bring the situation under control. As a result, a huge army soon appeared on the Shimabara Peninsula, with the number of soldiers swelling to around 120,000. The shogunate forces surrounded the ruins of Hara Castle and, while cutting off food supplies and initiating starvation tactics, lead a series of sieges on the castle. The attacks did not fare well though, due to a lack of tactical control over the troops. In addition, Hara Castle was proving to be more than just an abandoned ruin and was displaying the durability of the original structure built by Harunobu Arima. Because of these factors, the siege lasted for as long as three months.

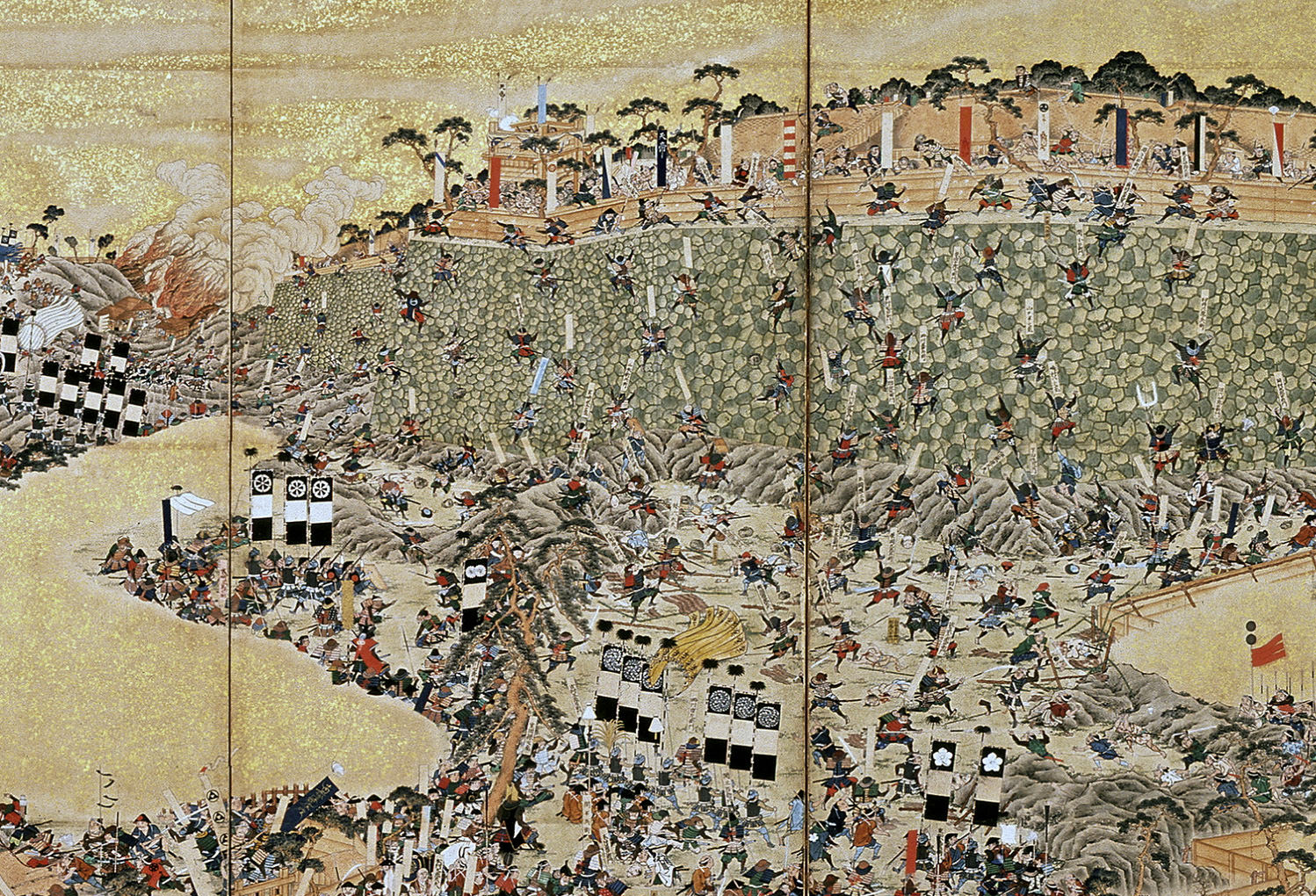

Folding screen illustrating the battle at Shimabara (property of Akizuki Kyodokan)

Folding screen illustrating the battle at Shimabara (property of Akizuki Kyodokan) The starvation tactics continued until almost all the food and ammunition in Hara Castle had been used up. At that point members of the rebel forces are said to have descended the sheer cliff wall behind the castle in order to collect seaweed from the ocean below. This was then used to supplement their meager provisions. When shogunate commander Nobutsuna Matsudaira inspected the bodies of rebels who had died out on the battlefield and saw that they had ingested nothing but seaweed, it convinced him that there were no more food provisions in the castle. He then decided to set April 12, 1638 as the day to launch a full-scale attack. The battle would begin haphazardly the day before, however, when daimyo leaders looking to take credit for victory began acting independently and launched offensives of their own.

The 120,000-man-strong shogunate army bore down on the rebel forces that had now run out of food and ammunition. Hara Castle fell in one day and the lives of almost all the people inside, Shiro Amakusa included, were lost. The destruction and slaughter by the shogunate forces was utterly relentless.

Recent excavations conducted at the site of Hara Castle have unearthed bones with gashes from sword blades, human remains with Christian medallions near their mouths and crucifixes made out of melted lead bullets. The artifacts discovered in these ruins still speak of the bitter nature of the battle and the religious faith of the people who took refuge inside the castle.

Lead crucifixes unearthed from the ruins of Hara Castle

Lead crucifixes unearthed from the ruins of Hara Castle“Leave no traces of Christianity...” The ruins of Hara Castle provide a glimpse into the actions of the shogunate when carrying out this order. To see that the remains could never again function as a castle, almost all the stones were removed from the foundation walls. Any remnants of the actual building itself were incinerated and buried under the stones of the demolished outer walls. The disposal was conducted with extreme thoroughness.

Responsibility for this uprising was placed on Katsuie Matsukura, the lord of the Shimabara domain, who was relieved of his position and later beheaded. The southern part of the Shimabara Peninsula, where all the local people had been eradicated, was subsequently repopulated with settlers from other parts of the country. In 1639, the shogunate banned Portuguese ships from harbors in Japan and the country was plunged into the long era of national seclusion.

Stone Foundation Walls of the Watchtower Destroyed (at the ruins of Hara Castle)

Stone Foundation Walls of the Watchtower Destroyed (at the ruins of Hara Castle)